“Archived Travels”

by Jennifer Motter

I will never forget the first class of my senior seminar at the University of Pittsburgh in 2018. The professor posed a simple question to the class, “why did you decide to become History majors?” For me, the answer was easy. I wanted to study history because knowing the past was how I made sense of the world around me. History helps answer questions about our world, both big and small—why did Spanish become the second most spoken language in the United States instead of French? Why did the United States not have a Catholic president until 1961? Why did blue jeans become a staple of the American wardrobe? Two years later, while watching a cooking show amid the world’s first Covid lockdown, I was unexpectedly brought back to my professor’s question. The host of the show, a traveling chef, explained that he loved sampling foods from around the globe because it helped him to understand the societies he visited more intimately. People’s selection of ingredients, their inclusion or exclusion of certain spices, and their choice of cooking implements all tell him something about the local culture and way of life. Thus, in the same way that I navigate life through history, he navigates it through food. And luckily for us, we were able to turn these ways of perceiving the world into our professions.

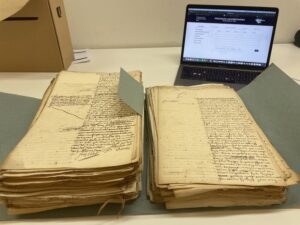

As a PhD Candidate in History specializing in the 17th century Dutch Atlantic salt trade, I spend a lot of time in the past. I read documents in an antiquated form of the Dutch language, learn the names of individuals who died centuries ago, and sift through accounts of grievances, legal disputes, and commercial contracts long after the ink used to record them has dried. But even as I work to reconstruct the world of the Early Modern salt traders, I find myself being drawn closer to the Netherlands in the present day.

My Fulbright Open Study/Research grant has given me the opportunity to spend the better part of a year traveling to Dutch archives located throughout the country. While the National Archive in the Hague (or Den Haag, if you’re a local) is home to more than 144 kilometers of printed and handwritten documents, the Netherland’s regional archives have impressive collections as well. Thus, I am fortunate enough to have a reason to go archives in cities that I might not have thought to visit otherwise. And in going to these smaller archives, I often learn just as much about their recent past and current present as I do about their history in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Take one of my favorite places, Middelburg, for example. Located in the southwestern province of Zeeland, this city houses the Zeeuws Archief—the regional archive that keeps many of the records originating from the surrounding area. You might be surprised to learn that in this collection, you’ll find more 17th century documents from the the neighboring city of Arnemuiden than you would for Middelburg itself. But why is this? It’s because the city was bombed by the Germans on May 17th, 1940, as part of World War Two. This attack which brought down nearly 600 buildings also destroyed much of Middelburg’s old archive. Fortunately, the city was able to rebuild itself and save their remaining historical records. Nowadays, as you take the 15-minute walk from the train station to the Zeeuws Archief, you can tell that Middelburg has a newer feel than, say, Amsterdam with its leaning houses and narrow alleys, but of course it remains as beautiful as ever.

Without looking into the disappearance of Middelburg’s 17th century manuscripts, I might not have learned of the city’s history during the war, and without researching the Early Modern salt trade, I might not have ever made the three-hour trip to Zeeland. But my work and the Fulbright has allowed me to explore and discover a region of the Netherlands that is relatively untouched by tourists. Similarly, my work has taken me as north as the city of Hoorn in West-Friesland, and as far east as Delden, laying less than thirty minutes from the German border. And with each archival trip, I learn something new about the country: how Northerners pronounce a harder “g” sound but drop the “n” at the end of a word; the way Zeelanders are proud of the way they’ve mastered their watery surroundings; or how German is more germane in Enschede than in Maastricht.

It goes without saying that each archive contains millions of stories, but it’s equally true that each archive is a story in itself. By consulting these archives and visiting their cities, one can learn what has shaped the local cultures, societies, and built environments. This is how I better anchor myself in the present—by keeping one eye on the past.